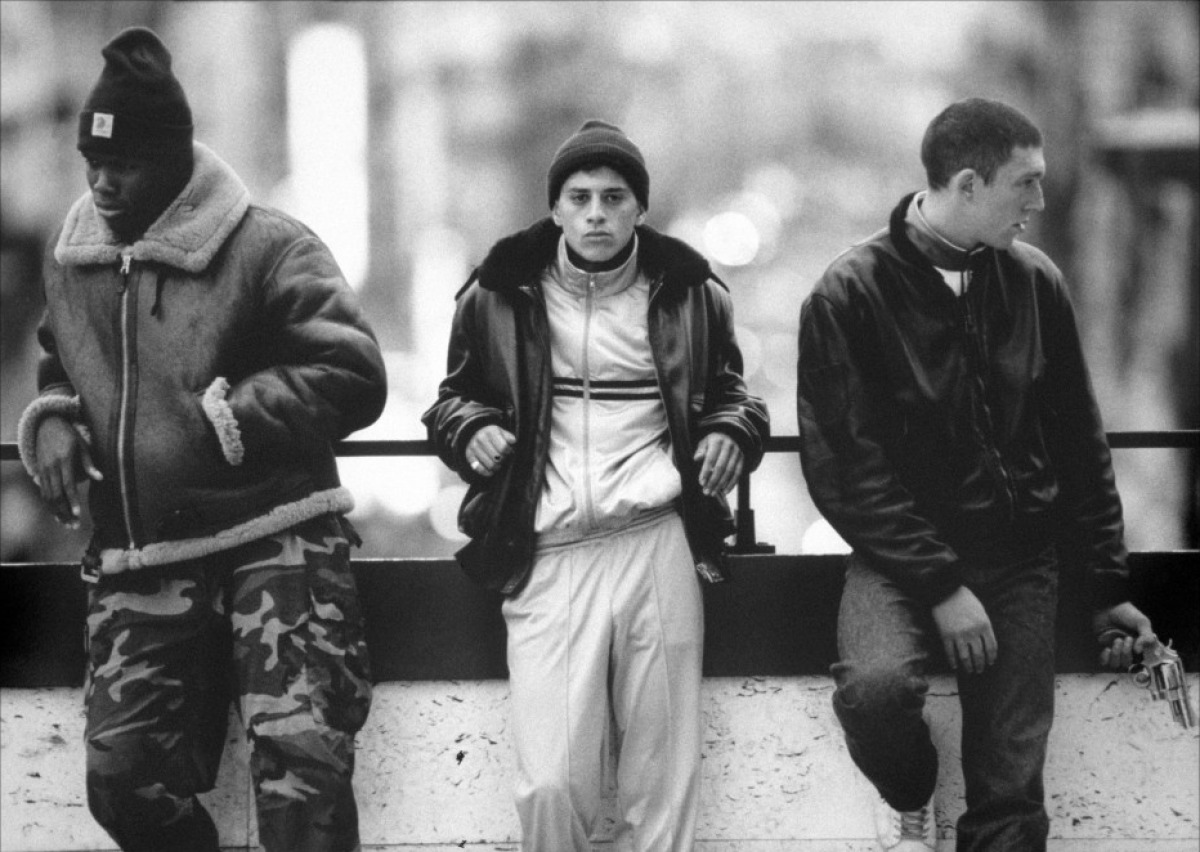

"Given that the Banlieue is also the principal

location of France's marginalised ethnic minorities, cinematic representations

of the Banlieue cannot easily ignore the representation of ethnic differences.” (Tarr, 2012) . This is true of La Haine as it was filmed on location it

gives a questionably true representation of life in the Banlieue. As La Haine takes place in the days

following a riot from the beginning the audience can see how the citizens,

especially the youth, of the Banlieue are unfairly targeted by the police due

to their ethnicity. It has been reported that people have died from police slip

ups whilst being held in custody and police brutality, this is also shown in La Haine “in one famous scene, two policemen sadistically molest Hubert

and Saïd while a trainee officer watches.” (Vincendeau, 2012) . This is further shown in the ending of the movie when Saïd

and Vinz are stopped by the police for no reason resulting in Vinz being shot

accidently by the police officer. Such police brutality and harassment shows

how the French slogan of liberty, equality and fraternity does not apply to the

second generation immigrants.

Throughout La Haine there is

also the theme that the young people growing up in the Banlieue do not feel

that they fit into one culture, they are torn between being French and whatever

their parents culture may be. The boys also seem to have turned away from

choosing either identity and have looked to American culture instead. When we

enter Vinz’s house we see Jewish iconography throughout the house however, as

soon as we enter his room it is filled with American iconography. “Vinz does a De Niro imitation (“Who you talkin' to?”). There's

break-dancing in the movie. Perhaps they like U.S. culture because it is not

French, and they do not feel very French, either.” (Ebert, 1996) . This point that

Ebert makes can be evidenced further through the dj set in which two different

generations songs are mixed together to perhaps signify the torn identities. The

way in which their identities are torn signifies that they do not feel part of

the fraternity that France expresses every French citizen is a part of.

In

conclusion it is apparent that the way in which La Haine portrays life in France shows that liberty, equality and

fraternity is not the case for everyone. As for mentioned the film shows how

racial inequality is very apparent not only in the banlieues but also in the

cities as well. The alienation of the boys in Paris is signified through the dolly

back zoom and the whole film being in black and white shows the bleakness of

there lives.

Student

Blog:

The

student blog https://up747885.wordpress.com/page/2/

in my opinion is excellent. Its layout is very engaging and easy to follow with

many pictures and video clips to break up the text. It shows lots of evidence

of research and subject knowledge of the films especially in the post ‘Is

Humanising Hitler Problomatic?’

Bibliography

Ebert, R. (1996,

April 19). Hate (La Haine). Retrieved April 2015, from RogerEbert:

http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/hate-la-haine-1996

Kassovitz, M.

(Director). (1995). La Haine [Motion Picture]. France.

Tarr, C. (2012). Reframing

Difference: Beur and Banlieue Filmmaking in France. Manchester:

Manchester University Press.

Vincendeau, G.

(2012, May 8th). La haine and after:Arts, Politics, and the Banlieue.

Retrieved from Current : http://www.criterion.com/current/posts/642-la-haine-and-after-arts-politics-and-the-banlieue